Visiting Exile: Self and City

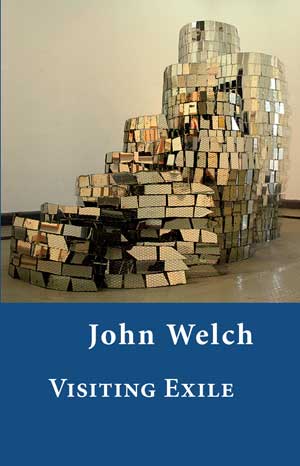

‘Visiting Exile’, my most recent collection, came out from Shearsman in October 2009. The Shearsman website describes it like this: ‘In this new collection John Welch returns to his longstanding preoccupation with the inner city and its diversities, fuelled in part by his own past experience as a teacher working in multicultural education. 'Out Walking' (which was the title of his first collection back in the 1980s) the poet's trajectory across the city is informed by London's imperialist past, by the 7/7 bombings, and by a sense of the complexities and ambiguities inherent in a deeply felt involvement with the Other. A recurring presence in the poetry is 'All Dressed Up and Nowhere to Go', a sculpture by the London-based Lebanese artist Souheil Sleiman comprising hundreds of fragments of broken mirror woven together to represent a group of tower blocks, taken here to represent, among other things, the self-regard and inherent fragility of 'the City' in its recent incarnation’.

‘The poet’s trajectory across the city’: there’s a movement from personal reminiscence to something more general, embodied in the figure of the walker; an attempt perhaps to make a bridge from one to the other? Entering the city: a symbolic act – and there’s the taking possession through the act of writing, but also through movement, especially moving through it on foot with intervals of public transport. You can enter at any point you like and then move about in it, movement as a kind of improvisation, making random, darting movements while perhaps holding to an overall direction. The nature of this passage is akin to the poetic process with its unpredictable twists and turns, walking a line that isn’t there. This liminal moment, crossing a boundary and entering, was traditionally profoundly significant, but where is the edge? The traditional city does have an edge, a wall with gates set in it, and a centre is implied, with its sites of especial ritual significance. But now there is a notion of the city endlessly duplicating itself – like the seven identical old men Baudelaire sees when out walking, in his poem ‘Les Sept Vieillards’. London is notable for its lack of an edge and this was something that preoccupied me in my teens when I started to write. And there are in practice two sorts of walking – there’s moving along feeling delightfully self-contained, free to roam, turn down any road or alleyway that looks interesting and being taken up with a sense of meaningfulness; but there is also plodding along, just keeping going on and on and on, like the boy in the dream I described in ‘Dreaming Arrival’. And now, of course, everywhere you go there are the cameras.

Preoccupied with the notion of a ‘promised city’, a childhood memory here from really quite early when reading, or at least dipping into, ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ and being deeply affected by its vision of the ‘city on a hill’; the city as a place of pilgrimage – Jerusalem or Rome. Starting to write in my teens, I was taken up with The Waste Land, Eliot’s London – ‘Barges sail . . .’ and ‘Inexplicable splendour . . .’. Later there were cities in Pakistan and India, especially Lahore, where I spent a gap year attached to a school in Pakistan, an eighteen year old walking and cycling round the city. I described this in ‘Dreaming Arrival’: ‘I had a dream the other day where there was a town map showing among other things an athletics track and over to one side of the track it marked the site of ‘a monument to the unauthorised self’ and it said – this was all printed on the map – that any one who had an ‘opinion’ as to where the monument might be should get in touch with . . . but there the dream ended. . .As I was writing it down I remembered that town map I bought back in 1960 when I was eighteen and living in Lahore, in Pakistan. Now, thirty years later, wanting to make another attempt at inhabiting it, I spread it out. Drawn up, I am sure, before Independence, and by the look of it not revised subsequently, it is an exotic document in its way. There are areas marked Female Jail, Military Poultry Farm, Criminal Tribes Settlement . . . Near the top is the Old City with its seven gates, a roughly pentagonal shape of almost solid brick red, the buildings being packed so close together that to show all the alleyways would not be possible on this scale. I used to cycle up there from the school. I had a drop-handled racing bike I’d brought with me, or I might hire a bike from the old man sitting under a tree just outside the school’s back entrance who rented them out by the hour. I would cycle up Mall Road, a thoroughfare into the modern part of the city, Having found somewhere to leave the bike I would turn into Anarkli, the main bazaar and then dive in through one of the city gates and once inside the old city I could lose myself in the maze of alleyways, filled with the intriguing smell of urine, spices, frying food. This was where my taste for wandering around cities first developed. But there was another thing – at the edge of the old city was the Badshahi mosque, said to be the biggest in the world. You left your shoes and stepped into the courtyard and here, in total contrast to the crowdedness you’d left behind you, was an enormous open space, something very plain and clear. And then if you felt like it you could climb up a narrow spiral staircase to the top of one of the minarets and from there you had a wide view, the river Ravi and beyond it the enormous plain. Since then I’ve walked round many in many different cities, out on my own and always with a notebook in my pocket. It’s as if I were waiting for someone to greet me. And this monument? Well maybe the thing is that it keeps on moving about and it is all only a matter of opinion anyway.’And then inhabiting London for myself, when I recovered myself following a breakdown and was roosting in my bedsitter. A few years later, a year spent in Lyons – because ‘Visiting Exile’ is among other things the poem I was trying to write around that time. In part the product of days spent walking around the Vieux Lyon, and up on the Croix Rousse, it was

very long, with a sort of driving rhetoric which came in the end to overwhelm it.As for migration, movement into cities and contact with otherness, my teaching career was spent working mainly with Asian children, recent arrivals to London. In one section of ‘Visiting Exile’ the poet Ghalib’s Delhi is invoked. It’s the idea of a city as something whole and perfect, held in the mind, which is then torn apart. Delhi in its heyday had been one of the world’s great cities, a high point of Islamic culture. The old city of Delhi was sacked after the events of 1857. Running through the collection are all kinds of continuities, and a sense of past betrayals. There is for example this country’s imperialist ‘nation-building’ in Iraq in the early 1920s and, weirdly, the present Labour government’s attempt to reprise that, as if nothing had happened in between. Visiting the early 20th century ‘Durbar Court’ in the Foreign Office, on ‘Open Buildings Day’, there was something unreal about it, a sort of phantasmagoria, these tiers of statues rising up to the roof like a stage set. The statues were ‘classical’ – allegorical figures and representations’, grateful natives bearing tribute, like Aztec or Maya friezes or Egyptian wall-paintings – so maybe all empires are the same? Is it a curtain thrown over something, the shape of what is really there dimly discernible. Imagine it twitched away, as if one woke out of a dream and looked out over rooftops and all the way to the edge of this now unfamiliar city.

So there’s city as a place you are exiled from, or a place where as an exile you seek refuge, which is the other theme of the collection. But there may be something ambiguous in this preoccupation with the ‘other’. There is the desire for the other, desiring the other’s desire – because we are uncertain of our own after so much apparent gratification and so much uncertainty? Perhaps we wish to appropriate their indignation. The sequence does incorporate an unease about my position in all this. Which emphasises how personal this all is, because this sense of boundaries is partly about my own boundaries and sense of self, with problems about feeling a sense of separateness, about feeling infringed upon, feelings which go back a very long way. So in that sense ‘self’ is ‘city.’

There is a sense I have of the city is pervaded with a notion of something that has been brutally suppressed in order to make it. ‘Civilised’ – the words means literally ‘living in cities’ of course – overwhelming the ‘primitive’. For me this is embodied in the frescoes for the Aldobrandini Villa by Domenicino, most of which are now in the National Gallery. They depict the achievements of the god Apollo. The god is shown attacking a succession of primitive, more or less defenceless creatures – the Cyclops, the satyr Marsyas, Daphne and so on. In one fresco, ‘Apollo and Neptune advising Laodemon on the Building of Troy’, the god appears as a celestial town planner while the New City rises, immaculate, in the distance. These scenes are depicted as if on tapestry hangings. At the foot of one of them and standing just in front of it, obscuring the fringed edge, is a burly dwarf, chained and staring out at the spectator, holding his manacled wrists in front of him. This then becomes a sense of the primitive, in its violence and pathos, subsisting in the present-day city.

The London bombings of 2005 are a presence in the book and there’s also a personal preoccupation with the Second World War and the Blitz. I was born in 1942 so have no real memories of the war itself, but I do remember its aftermath, in particular the bombsites scattered all over central London. They developed their own particular ecology, comprised of the plants that occupied the space and the birds that turned up there – as a child I recall the excitement occasioned by the appearance of such rarities as the Black Redstart on bombsites in the centre of the city.

In particular the book is pervaded by references to the London-based Lebanese artist Souheil Sleiman’s sculpture ‘All Dressed Up And Nowhere To Go’. This work comprises hundreds of fragments of mirror attached to a wire framework and is depicted on the book’s cover. At the time – he has since been obliged to move – his studio was in Hackney Wick in East London, one of those industrial areas where many traditional industries having moved out the premises have been occupied by artist’s studios. So the district was one of these crannies still existing in the city into which people such as artists can insert themselves. But not far away is the site for the 2012 Olympics. Souheil Sleiman has described how he started, as a student, working with textiles and he has become very interested in the idea of unravelling. ‘All Dressed Up’ is a glass tower, like a glass skyscraper that is unravelling. There’s a reference to the Twin Towers, to something apparently massive and solid which turned out to be vulnerable. He says he is also thinking of the rebuilding of Beirut. Previous work of his has explored the ecology of this and its effects on the surrounding landscape. At the same time in his piece is a sense of something has been taken apart and simplified. He has suggested there is also a reference to the banks of TV screens you used to get in shops, mirror fragments as the screens. Taking the city to pieces; trying to make the piece work ‘without supports’ – it’s fragile. And the traditional idea that someone reflected in a mirror is still there, in the mirror, after s/he has gone. . . At one point in the book it gets mixed up with Alexandria. ‘All Dressed Up’ having been selected as Lebanon’s entry for the Alexandria Biennale in 2007. The artist had to take the whole thing to pieces, pack it up send it off and then go out there to reassemble it. There are those cities one has never been to but which occupy a significant place in one’s imagination. Alexandria is one such, the city of a miraculous library that was destroyed. It’s about mixture – Greek and Arab.

The concluding section is titled ‘Yearn Glass’ and was prompted by that first experience of ‘All Dressed Up’ – next door to Sleiman’s studio there was a workshop ‘Yearn Glass Mirror Manufacturers. It seems almost too good to be true. Yearning for the image in the mirror, the self? But it is the genius of the mirror to divide and unite simultaneously, to combine total familiarity with an absolute strangeness. The mirror encloses within itself while paradoxically having no borders; it goes on for ever but has no depth. The dead shift, ever so slightly, in its chilly shallows so that a face in there can sometimes fall like a shadow across a face. This reflexiveness – can you break out of it?

Meanwhile it is every one of us each in our own fleeting intransigence. There’s the paradoxical way in which this multitude of mirror surfaces, instead of showing you ‘who you are’, breaks you up and turns you away as you become a multiplicity of surfaces and reflections. You get flatter, more and more insubstantial. There’s the reflexiveness characteristic of modern life, everything tending towards being about itself. And the title of Sleiman’s piece – expressing a moment of ideological uncertainty? Where on earth do we go from here?

There is a particular view, walking along the Northern Outfall Sewage Embankment in East London (NOSE!), and stopping perhaps near Bazalgette’s pumping station, a Temple of Sewage with its gilded cupola and Byzantine interior, where you look across waste ground towards Canary Wharf.. Distance bends into itself, and what we now call ‘the city’ is purely and simply a financial centre, a place of screen transactions. The ‘money’ involved is as insubstantial as a reflection, the weight and substance of coinage no longer present. These transactions have an insubstantial quality, figures flickering over a screen, and constitute a self-referential system (not unlike the post-structural notion of literature?) Which is maybe why a year ago it all went wrong, while somewhere at the end of a very long chain these transactions are translated into the realities of people’s actual lives. So there’s something here about flatness and the attempt to acquire substance in a two-dimensional world. The city contains difference but it is a reaching out to this that, paradoxically, ends by returning the self to itself, a possible healing through the prismatic radiance of the ordinary?

You can read Vahni Capildeo’s review of the book online on the Blackbox Manifold site at www.manifold.group.shef.ac.uk